Coumarin: Properties, Reactions, Production and Uses

What is Coumarin?

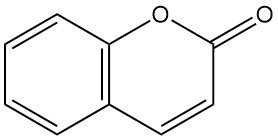

Coumarin, also known as 2H-1-benzopyran-2-one or 1,2-benzopyrone, is a natural aromatic lactone with the chemical formula C9H6O2. It is a colorless crystalline solid with a bittersweet odor like hay and is used as a fixative in perfumes.

Vogel first isolated coumarin from tonka beans (Dipteryx odorata) in 1820, and in 1868, William Perkin synthesized it via the Perkin reaction.

Coumarin is widely distributed in the plant kingdom; it is found in sweet clover, woodruff, cassia, melilot, lavender, balsam of Peru, and other plants at a concentration ranging from 87 000 ppm to 5 ppb.

In the past, coumarin was used as a food flavoring, particularly in conjunction with vanillin, however, its use in the food industry was banned in the United States in 1954.

Table of Contents

1. Physical Properties of Coumarin

Coumarin appears as colorless, shiny leaflets or rhombic crystals at ambient temperatures with a pleasant, sweet vanilla odor and a bitter, aromatic burning taste. It is very soluble in chloroform and pyridine, soluble in ethanol and ether, and slightly soluble in water.

The physical properties of coumarin are listed in Table 1.

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| CAS number | [91-64-5] |

| Chemical formula | C9H6O2 |

| Molecular weight | 146.14 g/mol |

| Melting point | 68-70 °C |

| Boiling point | 301 °C at 100 kPa 170.4 °C at 2.7 kPa 138.5 °C at 0.7 kPa |

| Density | 0.94 g/cm3 at 25 °C 1.178 g/cm3 at 100 °C |

| Vapor pressure | 0.13 kPa at 106 °C |

| Flash Point | 150 °C |

| Solubility in water | 0.25 g/100 g water at 25 °C 2 g/100 g of water at 100 °C |

2. Chemical Reactions of Coumarin

Coumarin undergoes typical reactions of the lactone of an α,β-unsaturated aromatic acid.

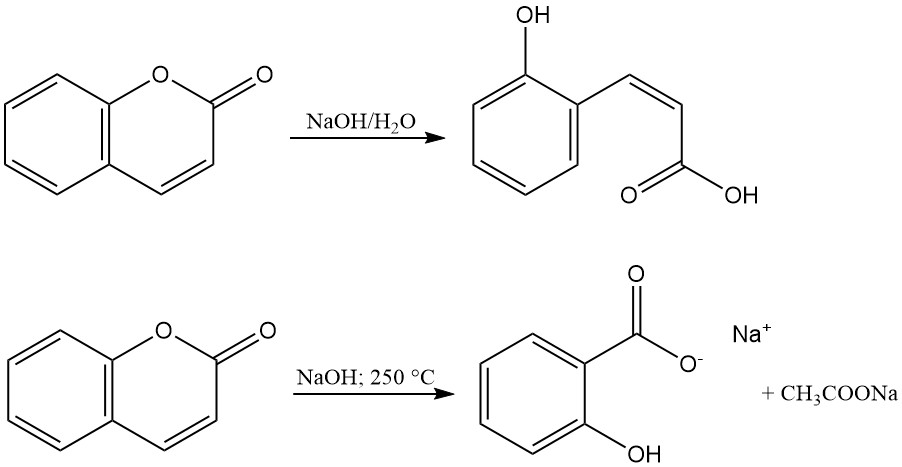

The lactone ring of coumarin is hydrolysed with alkalies to produce salts of coumarinic acid or o-hydroxy-cis-cinnamic acid. These salts are odorless and revert to coumarin through acidification. The reaction of coumarin with molten sodium hydroxide forms sodium salicylate and sodium acetate.

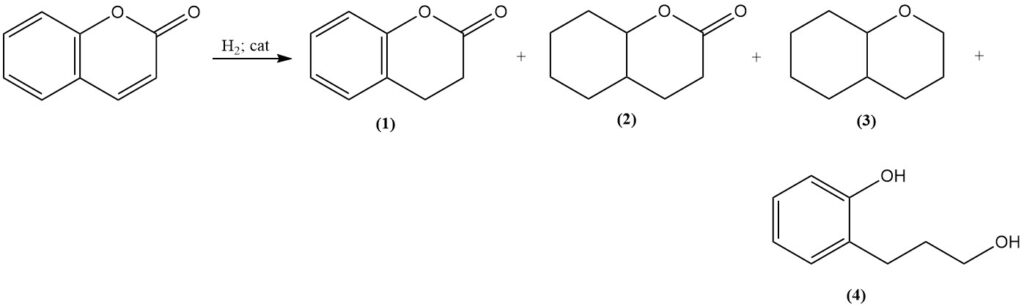

Catalytic hydrogenation of coumarin produces various products based on reaction conditions. Moderate conditions using Raney nickel catalyst form 3,4-dihydrocoumarin (1); however, increased temperature and pressure lead to the formation of octahydrocoumarin (2), hexahydrochroman (3), and polymerization products.

Selective hydrogenation to 3,4-dihydrocoumarin (1) can be achieved with a platinum sulfide catalyst, and hydrogenation at elevated temperatures using a copper chromite catalyst gives 3-(o-hydroxyphenyl)-1-propanol (4) with a very good yield.

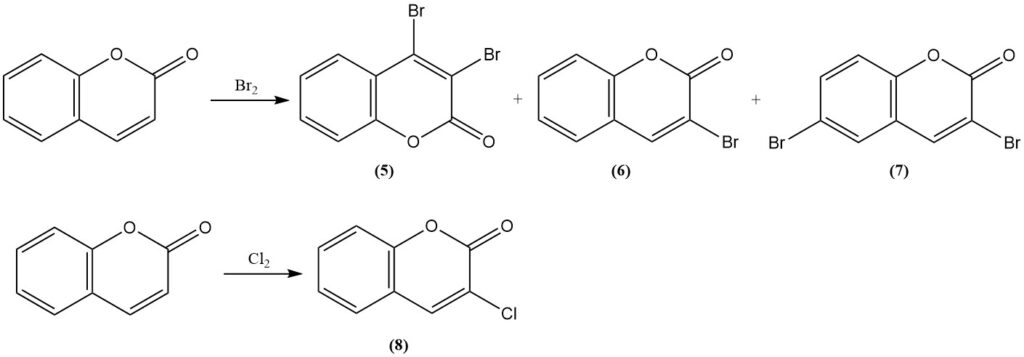

The reaction of coumarin with bromine results in 3,4-dibromocoumarin (5) under mild conditions. More rigorous conditions yield 3-bromocoumarin (6) and 3,6-dibromocoumarin (7). The reaction with chlorine produces 3-chlorocoumarin (8).

The reduction of coumarin with lithium aluminum hydride produces o-hydroxycinnamyl alcohol.

O-allylphenol is prepared by the reaction of coumarin with diborane.

Coumarin forms soluble sodium hydrosulfonates with sodium bisulfite, which can regenerate coumarin when acidified. This technique is used to purify crude coumarin.

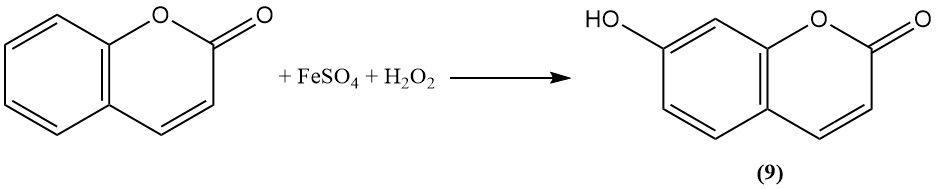

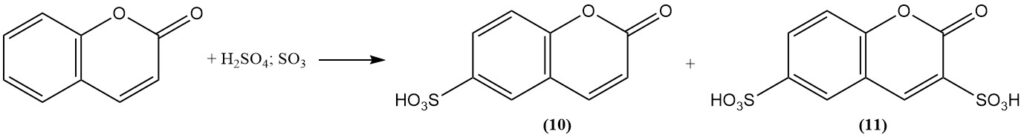

Oxidation with Fenton’s reagent converts coumarin to umbelliferone (7-hydroxycoumarin) (9).

Sulfonation of coumarin using fuming sulfuric acid forms coumarin-6-sulfonic acid (10) at moderate temperature and coumarin-3,6-disulfonic acid (11) at higher temperature.

Nitration with fuming nitric acid yields 6-nitrocoumarin (12). Methylation of coumarin with methyl sulfate or methyl iodide in the presence of sodium hydride produces methyl 2-methoxycinnamate (13). Boron trifluoride catalyzes coumarin photodimerization.

Coumarin can undergo other aromatic electrophilic substitutions such as halogenation, alkylation, and acylation.

3. Production of Coumarin

Until the late 1980s, coumarin was exclusively derived from natural sources by extraction from tonka beans and deer tongue. Today, it is produced chemically using o-cresol, phenol, and salicylaldehyde as starting materials. A diversity of synthetic pathways exist for coumarin synthesis from each of these raw materials.

3.1. Production of Coumarin From o-Cresol

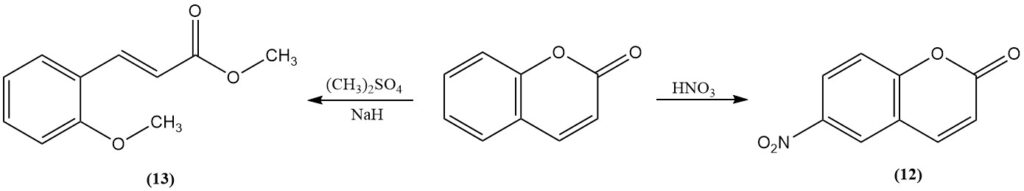

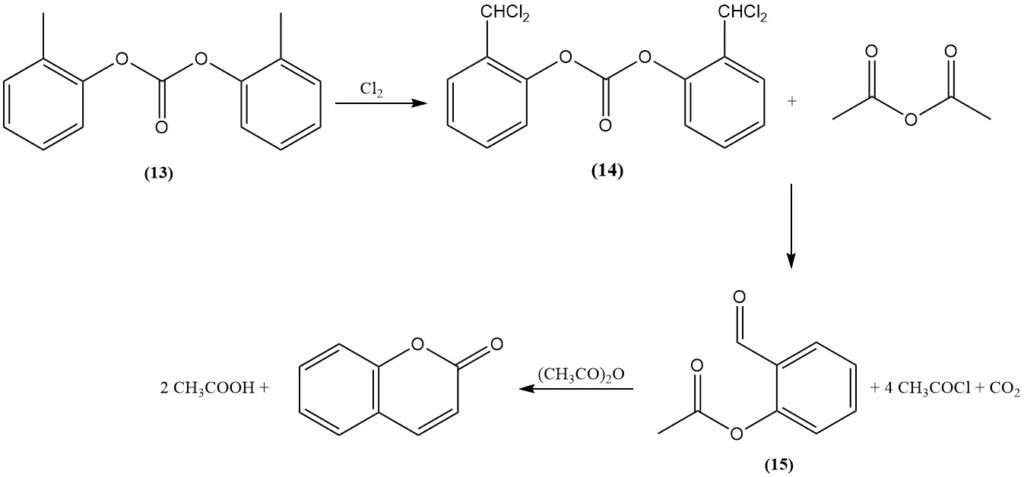

The Raschig process, discovered in 1909, is a primary synthetic route for coumarin from o-cresol. Initially, the phenolic hydroxyl group of o-cresol is protected through esterification with phosphate or, preferentially, carbonate (13). Subsequently, the methyl group is transformed into a benzal chloride intermediate (14) by dichlorination.

The resulting α,α-dichlorocresyl ester is then reacted with either an alkali acetate in a molten hydroxide or with acetic anhydride catalyzed by a metal oxide, such as cobalt oxide, to form o-acetylsalicylaldehyde (15), acetyl chloride, and carbon dioxide.

Finally, the cyclization of o-acetylsalicylaldehyde using acetic anhydride generates coumarin and acetic acid.

3.2. Production of Coumarin From Phenol

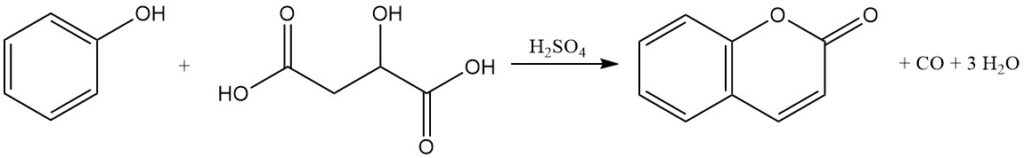

The Pechmann condensation, discovered in 1883, represents a primary method for coumarin production from phenol. In this process, coumarin is produced by the reaction of phenol with malic, maleic, or fumaric acids in the presence of concentrated sulfuric acid.

The Pechmann reaction is widely used in the synthesis of numerous coumarin derivatives. For example, the condensation of phenol with ethyl acetoacetate produces 4-methylcoumarin. Additionally, phenol can react with diketene to form coumarin.

Phenol reacts with specific acrylic acid derivatives to produce coumarin.

Coumarin is also produced by the reaction of phenol with 3-ethoxyacrylic acid chloride to produce phenyl ethoxyacrylate, followed by a cyclization reaction using sulfuric acid. Furthermore, coumarin is synthesized by the reaction of phenol with methyl acrylate in an acidic medium in the presence of air.

3.3. Production of Coumarin From Salicylaldehyde

Perkin Reaction

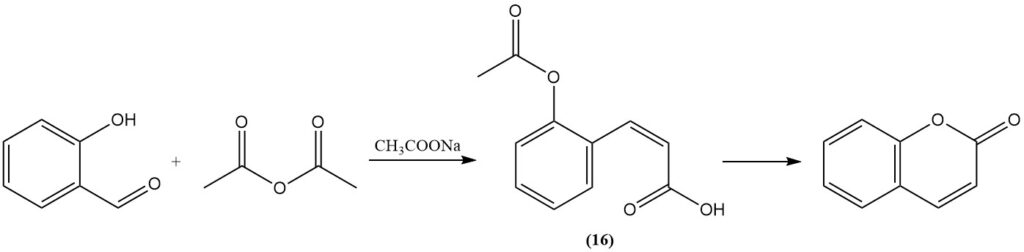

The Perkin reaction, initially discovered by Perkin in 1868, represents a classical method for coumarin synthesis from salicylaldehyde. This process involves the reaction of salicylaldehyde with acetic anhydride in the presence of sodium acetate as a catalyst. The reaction proceeds through the formation of cis-o-acetoxycinnamic acid (16) as an intermediate.

The Perkin reaction is important industrially, which is why it has been extensively studied and modified to enhance its efficiency. These modifications include the addition of iodine, metal oxides, or salts; the addition of pyridine or piperidine as catalysts; the replacement of sodium acetate by potassium carbonate or by cesium acetate; and the use of alkali metal biacetate.

Knoevenagel Reaction

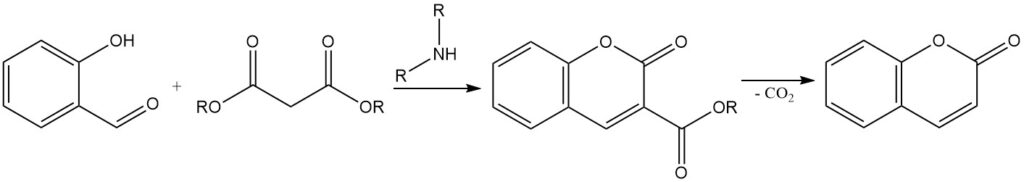

The Knoevenagel condensation is a reaction to synthesize 3-substituted coumarins from salicylaldehyde. It involves the condensation of salicylaldehyde with active methylene compounds, such as acetoacetic acid, malonic acid, or cyanoacetic acid, in the presence of an organic base catalyst such as ammonia, pyridine, and primary and secondary amines.

The resulting 3-substituted coumarin can be converted to coumarin by the removal of the substituent group. For example, coumarin 3-carboxylic acid, obtained from the condensation of salicylaldehyde with malonic acid, can be decarboxylated by heating up to 290 °C to form coumarin.

A mild decarboxylation reaction with a better yield can be achieved using mercuric salts.

3.4. Other Methods

Alternative synthetic routes to coumarin include the cyclodehydrogenation of oxocyclohexane propionate and the dehydrogenation using elemental sulfur or vapor-phase catalysis with metal oxides of 3,4-dihydrocoumarin, which is obtained from the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of 1-indanone.

3.5. Purification of Coumarin

Synthetic coumarin needs to have high purity to be used for perfume. Conventional purification methods include fractional distillation under reduced pressure and crystallization from solvents like methanol or ethanol.

Additional treatments before the distillation process include the following steps: heating the crude coumarin with concentrated sulfuric acid, neutralization, and water washing; dissolution of the washed product in concentrated sulfuric acid followed by oxidation; and refluxing with aqueous sodium hydroxide with subsequent organic phase separation and washing.

Vacuum azeotropic distillation with polyhydroxy alcohols, such as triethylene glycol, is an alternative purification method. Zone melting techniques have also been reported for coumarin purification.

4. Uses of Coumarin

Because of its distinctive sweet aroma and stability, coumarin is used as a fragrance ingredient in perfumes, soaps, detergents, and lotions at concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 2.4%.

Frequently paired with herbaceous scents, coumarin is integral to the composition of fougère and chypre fragrance types. It is used as a fixative to enhance the longevity of natural essential oils, such as lavender, citrus, rosemary, and oak moss.

Beyond perfumery, coumarin imparts pleasant aromas to household products and industrial goods while masking unpleasant odors.

It is also used as a medium in laser dyes and a sensitizer in older photovoltaic technologies.

Coumarin and its derivatives have been explored for potential therapeutic uses, including the treatment of schizophrenia, microcirculation disorders, angiopathic ulcers, high-protein edemas, and cancer.

It is used as a drug for the treatment of high-protein lymphedema and for improved venous circulation, and has been tested in clinical trials as an antineoplastic

Coumarin has been shown to be active in propigmentation and slowing hair loss. A coumarin derivative has been employed in polarizing light-emitting crystals.

Today, coumarin is banned for use as a direct food additive; however, it is used as a tobacco flavor, and it is also used in the electroplating industry.

It is important to mention that while coumarin-derived compounds like warfarin are potent anticoagulants, coumarin itself is not an anticoagulant.

5. Toxicology of Coumarin

Coumarin, a natural substance found in high levels in Cassia bark (a type of cinnamon), poses health risks through ingestion, inhalation, and eye contact, with acute overexposure potentially being fatal. It showed moderate toxicity to the liver and kidneys in animal studies.

Human exposure mainly occurs through skin contact with fragranced products and oral ingestion from foods, pharmaceuticals, and tobacco. While the skin absorbs coumarin readily, oral absorption is rapid, and the exposure route significantly impacts blood levels and toxicity.

Humans primarily metabolize coumarin into the non-toxic 7-hydroxycoumarin, and unlike some animals, human lungs do not produce harmful byproducts even at high doses.

Animal studies indicate that high dietary exposure to coumarin can lead to decreased food consumption, reduced body weight, and liver changes, with very high doses being lethal. In humans, coumarin exposure from various foods and pharmaceutical uses (up to 7000 mg/day) has been linked to infrequent and often reversible hepatotoxicity.

While some deaths have been reported, confounding factors make direct causation difficult to establish. Pure coumarin does not cause skin sensitization, but impurities or derivatives can. It has significantly lower anticoagulant activity than warfarin and is not associated with birth defects or adverse reproductive effects in humans.

Long-term animal studies primarily show decreased food consumption and liver toxicity, with non-metastatic liver tumors in rats at very high doses and lung tumors in mice from high bolus doses, but not dietary exposure.

In humans, occupational exposure to coumarin dust may cause respiratory irritation, and it can be a weak skin sensitizer. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies coumarin as Group 3, meaning it’s “not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans.”

Coumarin is not mutagenic, does not bind to DNA, and is not genotoxic. It has even shown protective effects against certain mutations and potential antioxidant and antineoplastic properties. Due to its relatively low toxicity, specific overdose management protocols are limited, focusing on general measures and monitoring.

Coumarin also exhibits low environmental toxicity and is expected to degrade readily.

For the full and comprehensive article about coumarin toxicology, please visit the following link.

References

- Coumarin; Kirk‐Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. – https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/0471238961.0315211302150919.a01.pub2

- Coumarins. – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780123864543007983

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B0123694000002696

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mnfr.200900281

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780124095472126204

- https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Coumarin